Beyond the Border: America’s H-1B Crisis

An investigation of public data sheds light on how the tech sector’s growing reliance on H-1B visas is reshaping the U.S. labor market and fueling a fierce debate over immigration policy.

While public debate often fixates on the southern border, a quieter, though no less consequential crisis is unfolding within America’s immigration system.

H-1B visas have surged in the U.S. tech sector over the past 15 years, transforming a program designed to fill temporary labor gaps into a cornerstone of a key American industry.

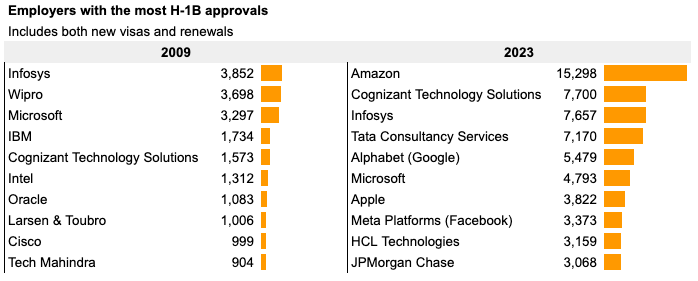

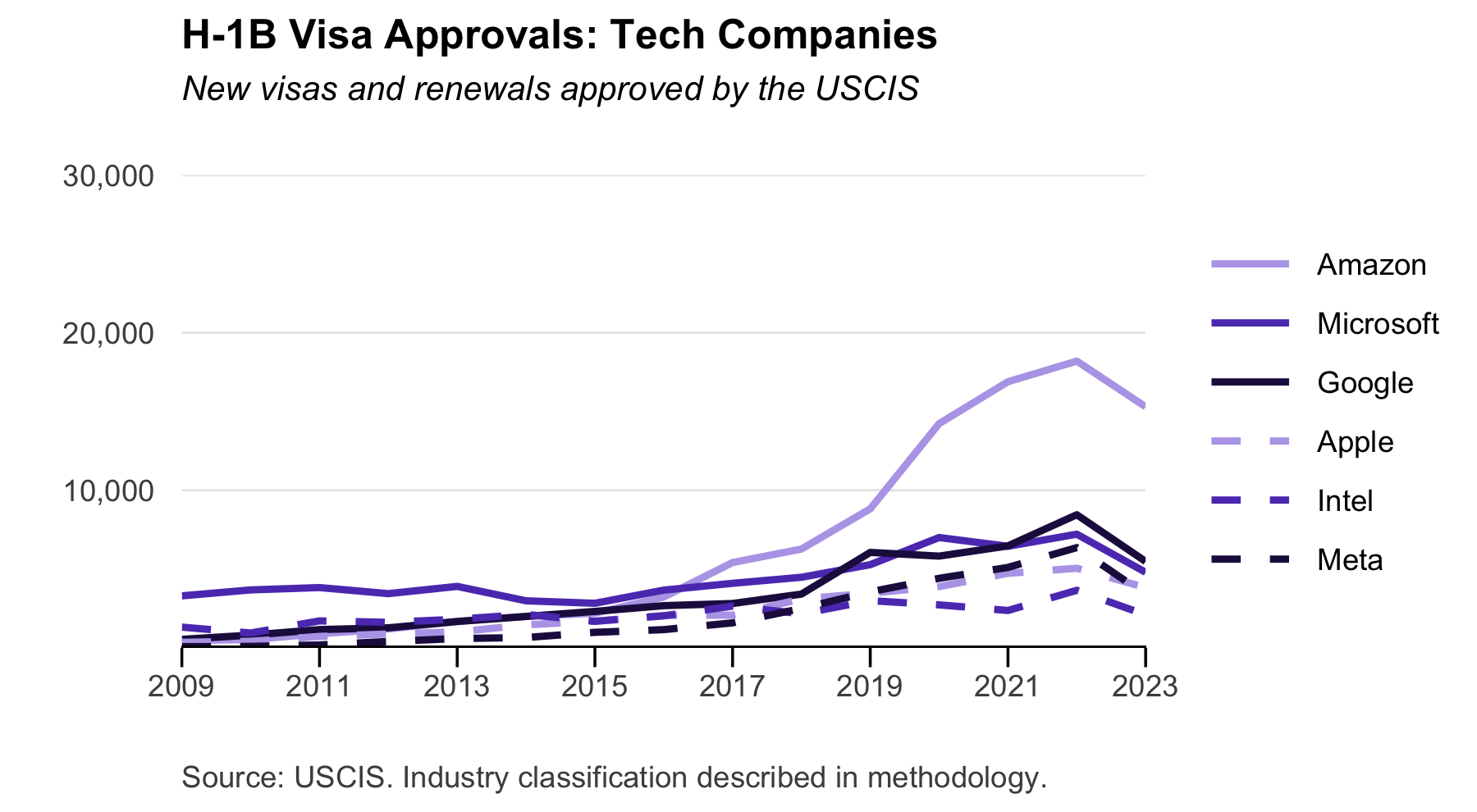

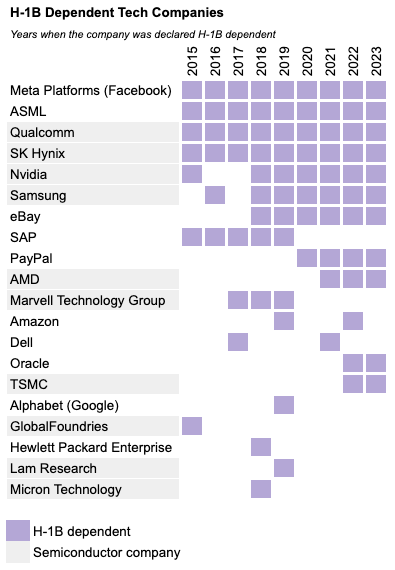

Between 2009 and 2023, big tech’s use of H-1Bs quadrupled. Half of the top ten H-1B employers are now tech companies, and in a sign of growing reliance on foreign talent, 20 major tech companies have declared dependency on the program since 2015.

Despite its modest scale, the roughly 120,000 new H-1B visas issued each year wield outsized influence on the U.S. economy - especially in the AI and semiconductors fields, where global talent is vital to maintaining the technological edge that underpins key pillars of U.S. foreign policy.

This investigation into data from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services and the Department of Labor reveals a system under strain, caught between rising isolationism and an industry racing to stay ahead in some of the world’s most consequential technologies.

Washington’s response, the data shows, is unlikely to ease the tension. Proposed reforms are poised to fall short of addressing the new reality of H-1B usage, and without broader immigration reform, the chance at permanent residency for many H-1B workers remains scant.

Each year without reform, hundreds of thousands of skilled foreign workers are funneled into a deepening backlog, leaving many to wait decades for a lasting place in a country whose future they’re helping build.

The ‘outsourcing visa’ goes to Silicon Valley

For more than 35 years, the H-1B visa has been the gateway for high-skilled workers entering the United States. The program allows for an initial three-year stay, with the possibility of a three-year extension. Although tens of thousands of companies file petitions each year under an 85,000 annual cap (with additional exemptions for academic and nonprofit organizations), two industries have come to dominate the field. IT and professional services staffing firms, along with tech companies, account for a quarter of all H-1B visas issued over the past 15 years.

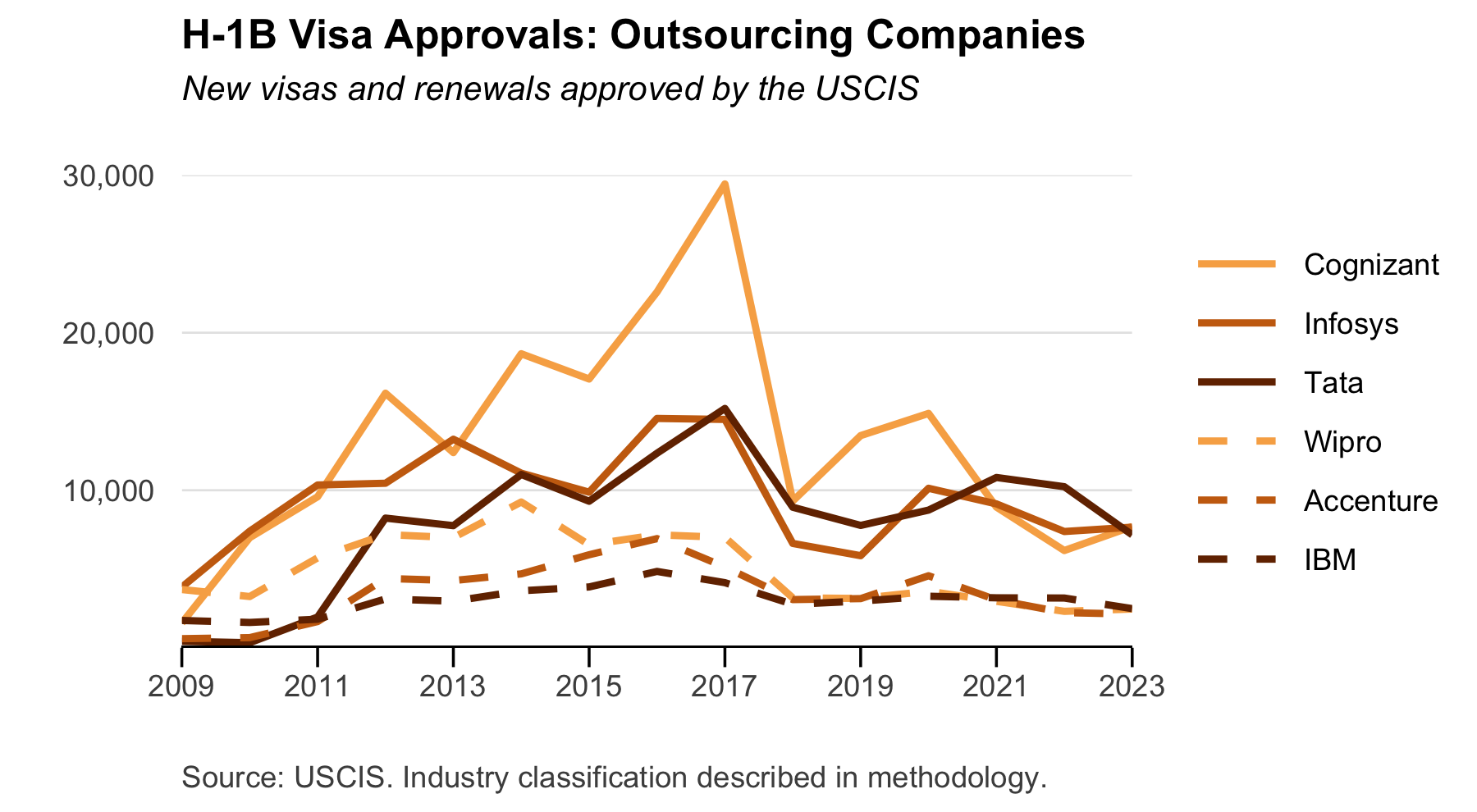

A decade ago, the most predominant H-1B companies where staffing firms, often headquartered overseas. In 2012, just 30 such companies claimed almost 48,000 visas - more than half of the annual cap - drawing bipartisan criticism of offshoring and earning the moniker “outsourcing visa.”

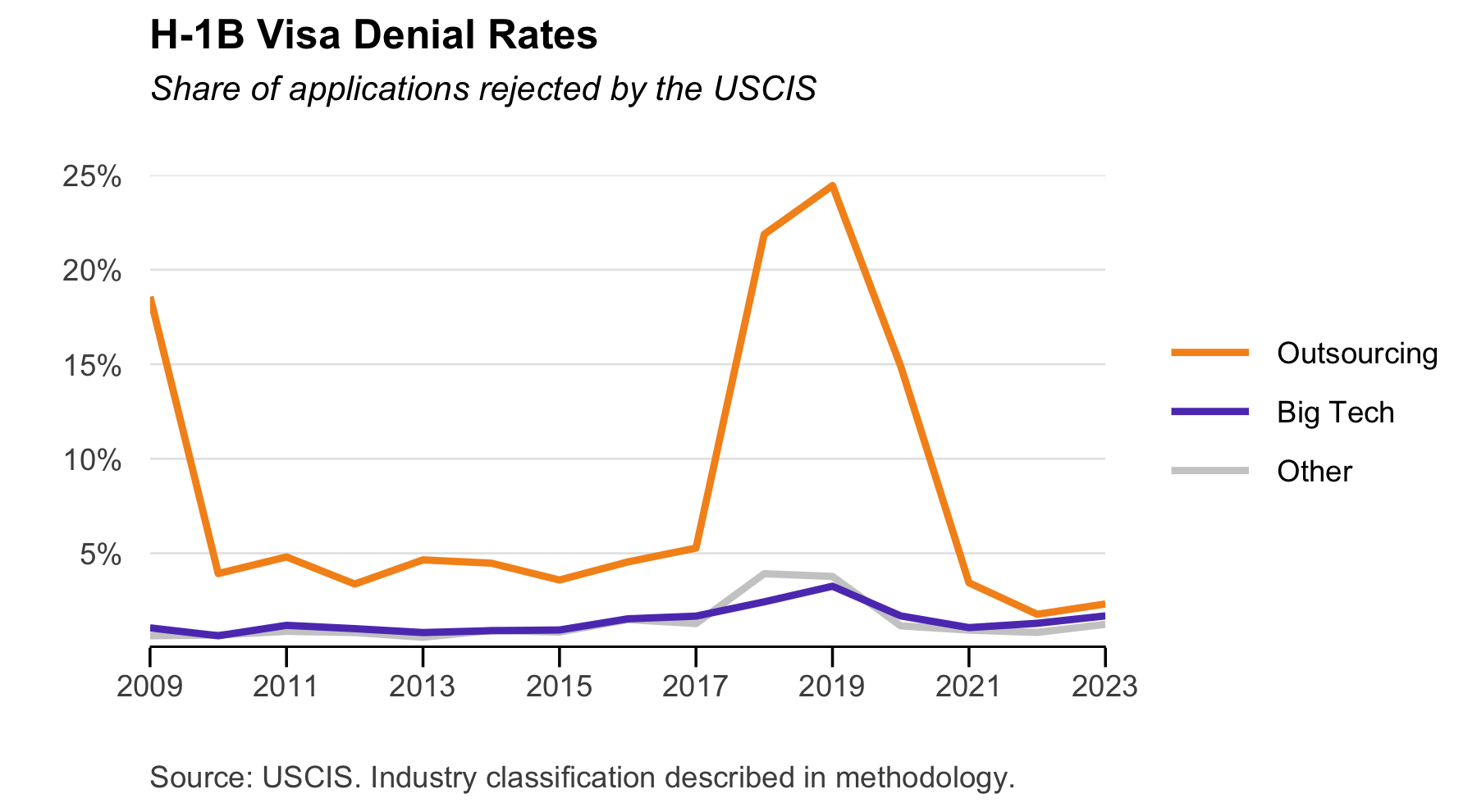

The tide began to shift during the Trump administration. Under the “Buy American and Hire American” directive, the government began to reject H-1B petitions at higher rates than ever before. In 2018, overall denial rates (including both new visas and renewals) more than doubled, rising to 15% from 7% the year before.

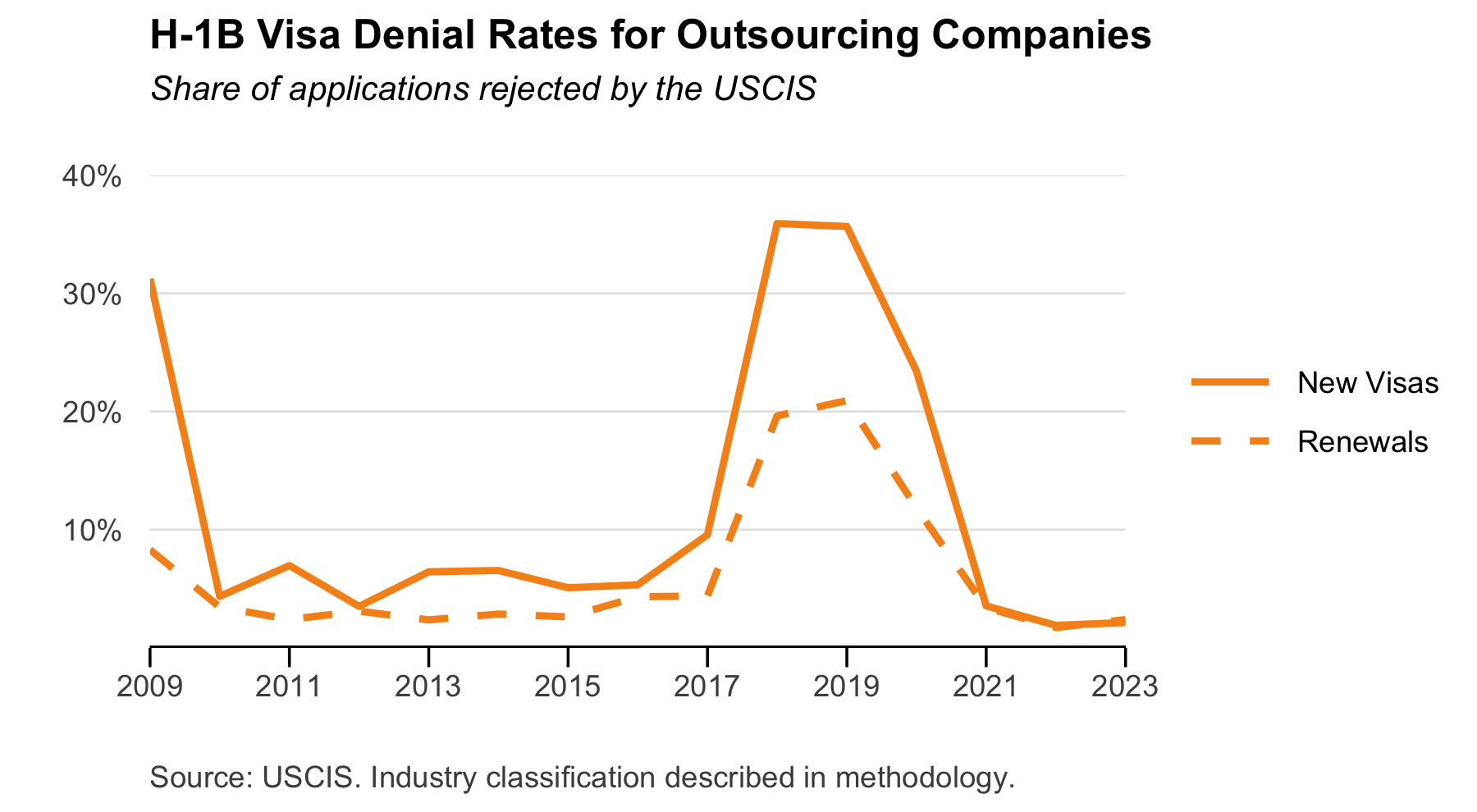

Outsourcing companies were hit hardest. Their denial rate surged from 5% in 2017 to 22% in 2018, peaking at 24% in 2019. First-time applicants bore the brunt: the administration rejected roughly 1 in 3 new H-1B petitions from outsourcing companies in both 2018 and 2019, and nearly 1 in 4 in 2020.

Meanwhile, major tech firms were largely unaffected. Denial rates for the sector’s largest companies remained flat, peaking at just 3% in 2019.

Instead, tech’s use of H-1B visas skyrocketed. Between 2009 and 2023, total approvals for big tech companies quadrupled, with half of that growth occurring during the Trump administration. Annual visa approvals for Amazon, Meta, and Google all more than doubled between 2017 and 2020.

More tech companies also began claiming H-1B dependency - a declaration to the Department of Labor that at least 15% of their workforce is on H-1B visas. Until recently, that designation had been largely reserved for outsourcing firms.

AI mania complicates reform

Washington’s preoccupation on AI could further fuel big tech’s growing use of the H-1B program. International rivalry - especially with China - has been one of the only priorities driving bipartisan action. In 2022, Congress passed the CHIPS and Science Act, which allocated $52 billion to semiconductor manufacturing, hoping to reshore an industry the US had pioneered.

Semiconductor firms are already among the H1-B program’s most prominent users. Of the 20 major tech companies that have declared H-1B dependency at least once since 2015, 11 operate in the semiconductor industry. Intel, though not formally H-1B dependent, ranks 15th among program’s top beneficiaries since 2009, securing nearly 32,000 visas over the past 15 years.

Yet even as H-1Bs help U.S. firms stay globally competitive, the program remains deeply controversial. Policy debates have scrambled traditional political divides. On one side, free-market advocates and industry-aligned Democrats argue that easing visa restrictions is vital for maintaining the nation’s technological preeminence, while left-leaning labor groups and far-right Republicans claim the program depresses wages, with some even calling it “theft” from American workers.

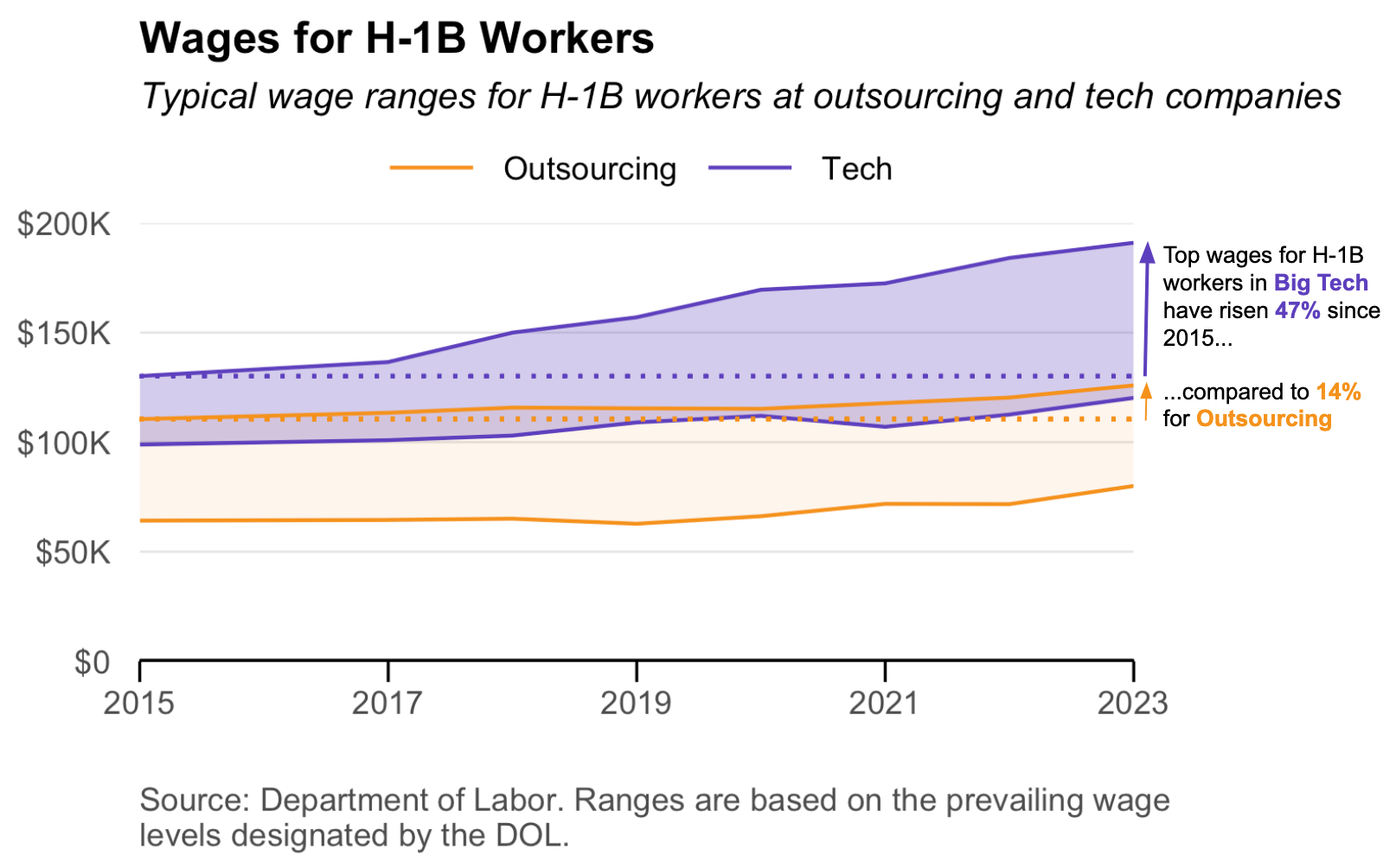

However, data suggests that many proposed reforms may miss the mark. Reform efforts typically focus on raising wage requirements, a strategy that primarily targets low-paying outsourcing firms, not tech companies.

Over the past 15 years, 72% of workers at outsourcing firms fell into the two lowest allowable wage brackets, compared to 54% in tech. In 2023, the median annual wage for H-1B workers in big tech was about $153,000, around 60% higher than the $96,000 median at outsourcing firms, with tech wages growing 33% since 2015 versus 26% for outsourcers.

Trapped in limbo

H-1B visas offer a bridge to working in the U.S., but it often leaves foreign workers - and their families - caught in a prolonged and precarious holding pattern.

Many H-1B workers apply for permanent residency, a process that can drag on for years or even decades. In 2021, 1.4 million employment-based visa applications languished in backlogs. For workers from India - who received nearly 3 in 4 H-1B approvals that year - the wait is estimated at 46 years.

Compounding the issue, H-1B visas are tied to specific employers, meaning if a worker loses their job, they must secure new sponsorship within 60 days or risk deportation. Meanwhile, more workers are vying for fewer companies. Since 2009, visa issuances have grown 70% while the pool of sponsoring employers has shrunk by about 20%, increasingly concentrated in a handful of industries.

Economic downturns further exacerbate the situation. During a 2022-2023 tech slump, layoffs surged: Amazon cut over 27,000 jobs, Meta 21,000, and Google more than 13,000. Although specific H-1B figures are hard to pin down, crowdsourced data from companies like TikTok and Tesla suggest that roughly a quarter of laid-off workers needed visa sponsorship.

Even those who keep their jobs face mounting pressure. When Twitter slashed nearly half its workforce in 2022, CEO Elon Musk demanded that remaining employees commit to “extremely hardcore” conditions of “long hours at high intensity,” otherwise risk getting fired. For the roughly 350 H-1B workers the company sponsored that year, and hundreds more from years prior, the choice was between accepting the ultimatum or gambling on a slumping job market, all under the spector of deportation.

That pressure is felt beyond sponsored workers themselves. H-1B visas cover spouses and children, leaving families to build lives in a state of limbo - spending more time away from the country they may be forced to return to, while building a life in a place that may not let them stay.

Together, these factors can trap foreign workers and their families in an overburdened and often capricious immigration system that fuels uncertainty and limits recourse.

As the nation grapples with reconciling rising isolationism amid the need for global talent, the fate of H-1B workers - and potentially America’s competitive edge - hangs in the balance.